|

|

Sunday, January 16th, 2011

The genius of Rivera Letelier's Art of Resurrection does not lie in the writing of the plot or the character development. There are events narrated that in aggregate form a plot, to be sure, and it's not (with sufficient suspension of disbelief) a bad plot, but not (by itself) a masterpiece either. The characters are pretty static (except for the two main characters -- and in their cases "development" consists largely of flashbacks sketching out their life stories, more to give context to the narrated events than as part of the main story) -- indeed one could say that in the narrated moment, the characters are almost wooden. The genius of Rivera Letelier's Art of Resurrection does not lie in the writing of the plot or the character development. There are events narrated that in aggregate form a plot, to be sure, and it's not (with sufficient suspension of disbelief) a bad plot, but not (by itself) a masterpiece either. The characters are pretty static (except for the two main characters -- and in their cases "development" consists largely of flashbacks sketching out their life stories, more to give context to the narrated events than as part of the main story) -- indeed one could say that in the narrated moment, the characters are almost wooden.

But somehow this does not work out to be a criticism of the book: it is precisely this almost-wooden quality where the æsthetic greatness of the work can be found. Rivera Letelier's calmly focused lens can zoom in onto his characters frozen in the moment of his story like bugs in amber* and communicate to the reader their rich complexities. Update: It occurs to me that this quality of woodenness and of masterful exploitation of it, is something the book has in common with Buñuel's Simon of the desert, the movie from which its cover illustration is taken.)

*(If not indeed birds in perspex)

posted evening of January 16th, 2011: Respond

➳ More posts about The Art of Resurrection

|  |

Friday, January 7th, 2011

A tantalizing bit of insight into Rivera Letelier's story-telling abilities is in this review of The Art of Resurrection, by Laura Cardona, book reviewer for La nación:

...As a young man, Rivera Letelier eaves-dropped on the conversations of the adults around him in Algorta, where his mother and his sisters (and likewise, later on, his wife Mari) balanced the family budget by serving meals. Every night, forty or more old miners would come by the house looking for a meal; young Hernán would pass whole evenings under the table, making note of every anecdote.

Cardona got this from Ariel Dorfman's Memories of the Desert, a 2004 account of traveling through the Atacama; she says Dorfman devotes more than a chapter to Rivera Letelier. This book is certainly going on my reading list...

(Found the Cardona review via Proyecto patrimonio's archive of writings about Rivera Letelier. Found the Dorfman book being remaindered by Amazon marketplace sellers.)

posted evening of January 7th, 2011: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Sunday, January second, 2011

Here is the state of play â…“ of the way into Our Lady of the Dark Flowers, as the striking workers, having marched from Alto de San Antonio to Iquique,  settle into their quarters at the Escuela Santa MarÃa* to wait for the mining companies' response to their demands: settle into their quarters at the Escuela Santa MarÃa* to wait for the mining companies' response to their demands: The primary characters are four friends who work at San Lorenzo, the salitrera where the strike was initiated: Olegario Santana, a 56-year-old loner and a hard worker, a veteran of the War of the Pacific; Domingo DomÃnguez, a barretero, the most gregarious of the group; José Pintor, a widowed carretero who is virulently opposed to religion and religiosity; and Idilio Montañez, a young herramentero and a kite-builder. In Alto de San Antonio, these four meet up with Gregoria Becerra, an old neighbor of José Pintor's when he worked in San AgustÃn, and her two children, 12-year-old Juan de Dios and 16-year-old Liria MarÃa. Gregoria Becerra was recently widowed when her husband was killed in a mining blast, and there is some suggestion (as yet undeveloped) of a romantic connection between her and José Pintor. Idilio Montañez and Liria MarÃa fall deeply in love with one another during the march to Iquique (Chapter 4). Her mother initially disapproves** but by Chapter 6 she seems resigned to it and even warming to the young man.

The male characters' occupations are central to their identities; Dominguo DomÃnguez is often referenced as "the barretero" and likewise for Idilio Montañez and José Pintor. I think Olegario Santana has not yet been referred to by his occupation, except maybe as a calichero. Here are my understandings of some of these terms, I'm not sure how accurate they are:

- Barretero is a worker at the mine who digs trenches.

- Carretero is a mechanic who works on the carts used for hauling caliche, the nitrate ore.

- Herramentero is (at a guess) a blacksmith.

- Calichero is a mine-worker; I think it is a generic term covering anyone who works at the nitrate mines. There are several words derived from caliche that occur quite frequently in the text.

- Particular is one of the jobs in the nitrate fields; I think it might refer to someone who works with explosives.

- Derripiador is one of the jobs involved in processing nitrate ore.

- Patizorro is (I think) another term for particular.

- Perforista: another term for barretero.

Some of this stuff is pretty specific to nitrate mining in Chile, I'm not sure how it could be brought over cleanly into English. Album Desierto has a great glossary of salitrera terminology.

*It is difficult reading (mostly in the present tense) about how excited the striking workers are, how happy and hopeful they are in the face of their hardships, when you know how the history is going to end up. **At one point Gregoria Becerra says her daughter "does not need any idilios"; Idilio Montañez' name means "love affair".

posted morning of January second, 2011: Respond

➳ More posts about Our Lady of the Dark Flowers

|  |

Friday, December 31st, 2010

Rivera Letelier is an absolute wizard of narrative voice, of person -- I wrote before about the shifts from third to first-person singular in The Art of Resurrection; something even more complex and initially confusing is going on in Our Lady of the Dark Flowers. This is quite possibly the only novel I've ever read which is told in first-person plural omniscient present.* The novel opens

with the narrator telling a story, set in the present tense, about 56-year-old widower Olegario Santana and his two pet vultures** -- he "is feeding" them, they "are emitting their gutteral carrion cries"... And it is initially quite jarring when the narrator backs off and shifts to "we" -- I believe the first place this happens is at the end of the sixth paragraph, where Olegario is walking to the mines -- something does not seem quite right, suddenly he meets up with a group of men who come up to him and "we tell him" that perhaps he has not heard, but a general strike was declared last night. Is "we" the group of men? That's what it seems like at first; but as the novel progresses, "we" becomes more general, it is the workers of the pampa as a general class. The narrator is not a singular person or a distinct group of people -- the group of men would not have been able to narrate Olegario feeding his birds -- but is rather the voice of the pampino community. By doing this Rivera Letelier includes you the reader as a member of that community and makes it very easy, after a little hesitation, to get inside the book. Thinking of the story as a movie: when the narrator is telling about Olegario feeding his birds (and throughout the book in passages where he is speaking about "he" and "them"), he is describing the action onscreen as you watch the movie -- the present tense makes this work -- but when he shifts to "we", you realize you are part of what you're watching onscreen.

*I can't think of another one. Can you? I can't imagine this has never been done before; still it is quite distinctive.

**Well I'm pretty sure they're vultures anyway -- they are called jotes, which I think serves as a generic way of referring to birds, not buitres -- but they are described as carrion birds with pink heads, so vultures. Possibly jot is a Chilean term for vulture. Vulture does seem like an unlikely bird to have as a pet; but I am leaving that to the side for now, suspending disbelief. ...And, confirmation! Googling around for jotes in the Atacama brings me to a page from the Museo Virtual de la Región Atacama, with pictures of a vulture, "Jote de Cabeza Colorada (Catarthes Aura)". Wiktionary lists jote as a Chilean term for turkey vulture.

posted morning of December 31st, 2010: 4 responses

|  |

Wednesday, December 29th, 2010

This week I've started Rivera Letelier's Santa MarÃa de las flores negras, Our Lady of the Dark Flowers -- the title is a reference to this anonymous poem, "The Dark Copihue, Flower of the Pampa", published in 1917 commemorating the 1907 massacre at Escuela Santa MarÃa de Iquique:

Soy el obrero pampino

por el burgués esplotado;

soy el paria abandonado

que lucha por su destino;

soy el que labro el camino

de mi propio deshonor

de mi propio deshonor

regando con mi sudor

estas pampas desoladas;

soy la flor negra y callada

que crece con mi dolor.

I am the pampino worker

Exploited by the owner;

I am the outcast, abandoned

fighting for his destiny;

it is I who lay the roadway

of my own disgrace

irrigating with my sweat

this desolate pampa;

I am the dark, silent flower,

flower that feeds on my sorrow.

A blind man** recites this poem in Chapter 3, among other folk poetry about the workers' struggle. (This seems like an interesting way of interweaving fact and fiction, since of course the poem was not written at the time the novel is set. The author is turning the poem into an element of his fictional world.) The red copihue is Chile's national flower; the poet (who Sergio González Miranda speculates* could be Luis Emilio Recabarren, fixture of Chile's left wing in the early 20th Century) sees a black flower growing from the blood and sweat of the pampino workers.

*Dr. González Miranda is a professor of sociology at the Universidad Arturo Prat in Antofagasta, and seems like a great source for poetry of the workers' movement in Chile; besides the linked article I also found a piece by him from 2003 called "Habitar la pampa en la palabra: la creación poética del salitre". Professor González Miranda's books are available from Ediciones LOM. **The blind poet might be, if I'm understanding a statement in Chapter 4 correctly, Rosario Calderón, listed by PoesÃa Popular as the author of PoesÃas Pampinas in 1900.... Ah -- no -- I missed a note in Chapter 3 that the blind man's name is Rosario Calderón "just like the famous poet who publishes his works in El Pueblo Obrero."

posted evening of December 29th, 2010: 1 response

|  |

Saturday, December 4th, 2010

I'm slightly surprised at (or surprised that I am surprised at) the reverent picture Rivera Letelier paints of the Christ of Elqui. I think my expectation going in was that he would be a Quixote figure; and there is that quality, a comedy of errors aspect to his mission in the desert.* But beyond that, his reverence is treated very respectfully, painted with a sincere, complex brush. Here is part of a sermon to the striking workers:

His arms open forming a crucifix, the intense dark of his eyes flaring up, he spoke to convince his congregation that the desert is

«Atardecer en Atacama»

por Andrés RodrÃguez Morado

the place where one feels oneself most absolutely in the presence of the Eternal Father: the most perfect spot for speaking with Him.

— And it is not for nothing; as the Holy Bible tells us, even Christ himself spent forty days in the desert before he came out to preach his good news. And even so, O my brothers: not everything in this world is evil. You, sirs, have something which is worth more than gold and silver put together. The silence of the desert. The purest, finest silence anywhere on the planet; thus the most conducive for each one of you, to finding his own soul, the most suitable for listening to his God, for hearing the voice of the Eternal Father.

* (This expectation may also have been shaped by the focus of my attention while I was reading and translating the first chapter, which does have a sort of broadly comic or slapstick tragic feel to it.)

↻...done

posted afternoon of December 4th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Translation

|  |

Thursday, December second, 2010

What is fundamental, o my brothers, is not our suffering; it is the way we carry this suffering down the path of our life.-- The Christ of Elqui

The Christ of Elqui says this at the end of his sermon in Chapter 15, a sermon which I am thinking tentatively of as his "sermon on the mount" (and it bears remembering that there was reference to a sermon on the mount in the first chapter...) It might also bear comparison with King's "I have a dream" speech -- although I'm having a hard time understanding the "Imagine" portion of the sermon, it seems more whimsical than heartfelt.

I love the quote and it strikes me as a distinctly Buddhist sentiment, indeed almost a direct paraphrase of something the Buddha said, though I cannot remember what specifically.

The occasion for the sermon is a memorial service on December 21st, the anniversary of the massacre at Santa MarÃa de Iquique (which I learned of a couple of years ago from Saramago's blog) and coincidentally, the day after Zárate Vega's forty-fifth birthday. Two books I am hoping will help me understand Chilean labor movement history are: Rivera Letelier's earlier novel Santa MarÃa de las flores negras, set in Iquique at the time of the strike; and Lessie Jo Frazier's Salt in the Sand: Memory, Violence, and the Nation. Also a Google search for history of nitrate mining in Chile produces some useful hits like this one.

posted morning of December second, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Salt in the Sand

|  |

Sunday, November 28th, 2010

I am falling into a pattern with reading/translating/revising The art of resurrection -- I think the best way to carry out these activities is in parallel, they strengthen and enhance one another. So far every chapter I read in full and translate a few pages of, the translation and revision process sends me off to read some more or to re-read and get a better grip on the story and on the author's voice, which in turn sends me back to revise and expand my translations of earlier chapters, and to forge outposts of translation in later chapters. (And of course blogging about is another activity in relation to the text, one which weaves in and out among and distracts from and contributes to these three.)

Chapter 8 introduces Magalena Mercado, the prostitute whom Christ has been searching for.

Dark, her hair was brown and her eyelids drooped over deep pupils. This was Magalena Mercado, her soft curves moved languidly and in the air behind her, fleeting, trailed the sensation of a wounded dove. And this sensation was strengthened by her gestures as it was by the falling cadence of her voice. ...

Like everything else about her, her age was a mystery. The men's guesses ranged from twenty-five, or a little more, to thirty-five, or a little less. Besides believing in God the Father, His Son Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit, she was a devoted follower of the Virgen del Carmen. In her house, in the room where she slept was an almost life-size icon, made from wood, always a candle was in front of it and little flowers made of paper hung from it.

The narrator goes on to discuss whether Magalena Mercado came to the north of Chile during a transfer of mental patients -- a "de-institutionalizing" I suppose it would be called. I need to get a better handle on the historical background here -- did that happen once in Chile during the twenties or thirties, or was it a common thing to have happen, or is it a fiction?*

What is certain is that her customers were generally surprised, disconcerted by the altar which was installed in a corner of the room where she plied her trade, so much so that some, the most devout among them, were inhibited, left without consummating the transaction. You see, the icon of the Virgin, about a meter 20 cm high, carved by hand, was of an overwhelming, breathtaking beauty. So Magalena Mercado took care: every evening before beginning to wait on her "parishioners," as she termed her regular customers, she would kneel before the Virgin, cross herself vigorously, and cover the icon's head with a square of blue velvet.

"See you soon, little lady," she would whisper.

And look at how these paragraphs -- immediately following the above -- could be a short story in themselves --

Although many had heard her say that she could not stand priests, and even less the priest at La Piojo, whom she claimed to know from the village where they had grown up, Magalena Mercado was scrupulous in attending every mass. She would arrive a few moments after the beginning of the service; stealthily, ghostly, walking on tiptoes, she would take a seat in the final row of pews, on the left.

The priest, for his part, a fat, rubicund man, the shy expression on his face disturbed by nervous tics, he became so furious he had a coughing fit -- frothing at the corners of his mouth -- when they told him that the devout prostitute claimed to know him. Generally, when he saw her entering the church, he would make as if he did not notice, would continue to say his mass as if he had not noticed her presence. But on some occasions, particularly on Sundays, when the flock was larger, his Bible in hand, his stole flapping, he would imprecate against her from his pulpit, reading the sixteenth chapter of Ezekiel, picking out two or three of the most severe verses. On the days when his bile was blackest, filled with rage, he would read straight through all of the verses, like a brutal, biblical artillery attack: Wherefore, O harlot, hear the word of the Lord... I will judge thee, as women that break wedlock and shed blood are judged... therefore I will gather all thy lovers, with whom thou hast taken pleasure... And I will also give thee into their hand... and they shall break down thy high places: they shall strip thee also of thy clothes, and shall take thy fair jewels, and leave thee naked and bare. They shall also bring up a company against thee, and they shall stone thee with stones, and thrust thee through with their swords. And they shall burn thine houses with fire, and execute judgments upon thee in the sight of many women: and I will cause thee to cease from playing the harlot, and thou also shalt give no hire any more.

(There is a very mildly interesting question to be raised about translating a passage which is quoting a third work, e.g. the Bible, which has been translated elsewhere and in many versions, which English version to use: what I did here and what I think works best in this case is to use the KJV translation, which fits very closely with the Spanish lines quoted in the book.)

*This is discussed at greater length a few chapters later. I was misunderstanding the meaning of enganche, it means "recruitment" and has a special meaning in the context of nitrate mining. The mental patients in question here were brought north by an enganchador, a headhunter who recruits workers for the salitreras from the south.

↻...done

posted afternoon of November 28th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Writing Projects

|  |

Friday, November 26th, 2010

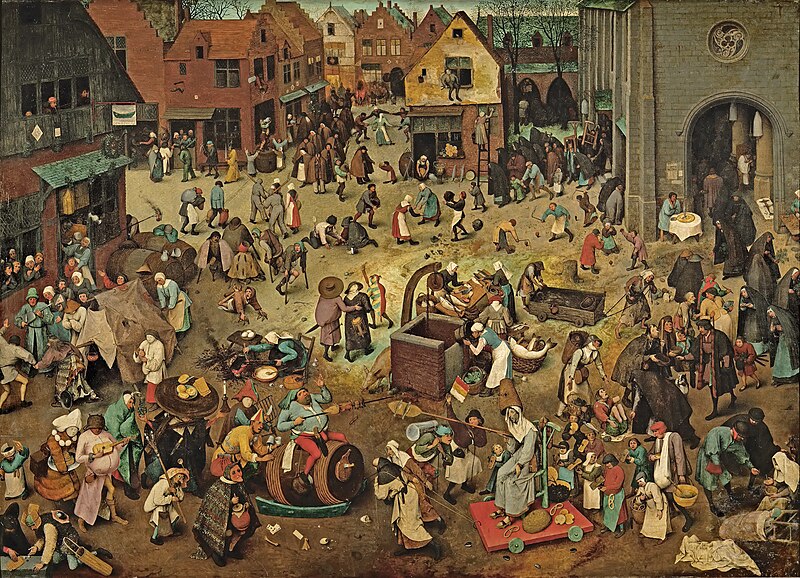

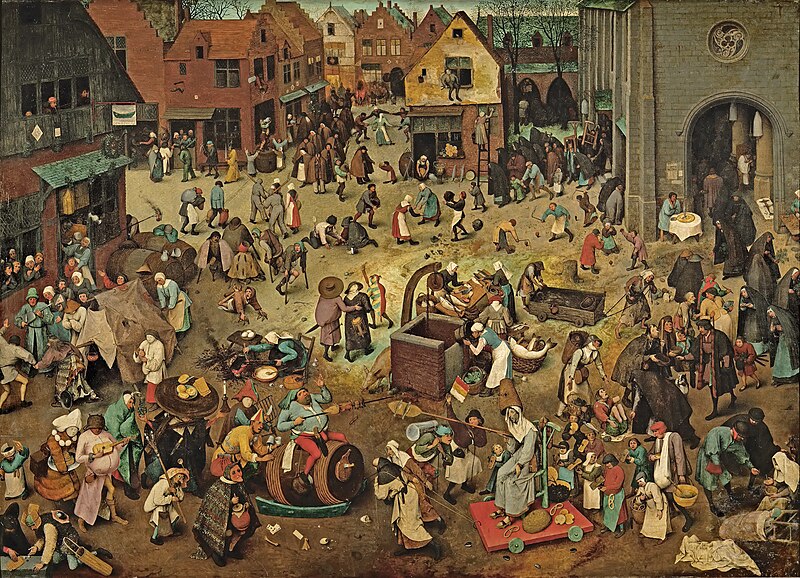

One key distinction to be made between El arte de la resurrección and a Bruegel painting, of course, is the direction, the cinematic quality of the former. If I stand looking at "The Battle between Carnival and Lent" it keeps me engaged, keeps my gaze shifting; but I am "directing" the movie by moving my gaze. Whereas here, there is clearly a cameraman showing us where to focus and what to move to the periphery. Check out this beautiful pan from the plaza to in front of the union hall, from chapter 7 -- reminds me a little of the opening shot from Heimat. The striking workers in La Piojo are waiting for their lunch, in front of the union hall:

Even from a distance one could see that chaos reigned, everything in a rambunctious disarray: a few kids, stick in hand, trying to keep at a distance the group of stray dogs that had assembled, attracted by the aroma of food, while a few well-built gaucho types were greasy with sweat, gathering and splitting wood for the fire; the group of women inside was sweating too, in their aprons cut from canvas flour sacks, their cheeks smudged with soot, they were ladling out dishes of the hot, steaming stew to the tight line of men, women, children who held out their chipped dishes, their faces long with hunger. The menu, like every day's, was a generous helping of chili beans -- one day with crushed maize, one day with peppers, which cooked on the other fire, smoking under a black skillet, seasoned with a colorful bloom of paprika.

The camera starts out away from the action, across the plaza; gradually it zooms in on the kids keeping away the stray dogs, then pans to men cutting wood (in my mental picture of this scene, the men are sort of behind the kids (vis-a-vis the pov) and a bit toward the union hall, the camera is moving across the plaza and a bit to the right) and then (continuing to the right, and swinging around) to the women cooking and to the people waiting; and the last word of the sentence is "hunger"! Then we linger lovingly on the food that's cooking, the centerpiece of this scene. (This and a passage a little later on when Christ is eating are beautiful food writing I must say -- this Rivera Letelier is extremely versatile.)

posted afternoon of November 26th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Projects

|  |

Thursday, November 25th, 2010

An example of the kind of sentence I was mentioning loving in Arte de la resurrección is near the beginning of Chapter 6, a description the people of Providencia (not, as I initially thought, a village in Elqui Valley, but a mining company town, a "salitrera," in the Atacama -- and referred to throughout the story as La Piojo, which I am understanding as Lousy*) gathering to await the Christ of Elqui. Listen:

The women came, their heads covered in dark bandannas, rosaries in their hands, a prayerful, focused halo softening the faces of these strong women, dutiful, capable of any sacrifice for their families. The children were running with their wire hoops, their tin wagons, with the rambunctious happiness of seeing something novel in the endless tedium which was the pampa, all the world they knew of; while those few men who were idling, who were spending the siesta on the hot stones by their front doors -- for most of them were together in the union hall, or keeping watch on the factory gate for strike-breakers -- came following the women and the children to see this novelty, ganchito, a Chilean Christ preaching in the desert. Even the most skeptical, the least credulous of them -- and the mine-workers were the most skeptical, the least credulous of anyone in the pampa -- those who could not believe that this layabout, this beggar could be Christ the King, that he was divine, could perform miracles -- "This Christ of the slums has never even healed a sleepy little girl, paisita" -- even these came to look away from his footprints with the disdainful grimace of the suspicious macho tattooed on their oblong faces.

At this hallucinatory siesta hour on the pampa, the sun was a burning stone at the center of heaven.

In the original the whole first paragraph is a single sentence, I could not avoid dividing it into a couple. You can spend a lot of time in front of that sentence as if it were a Bruegel, it repays multiple readings with new layers of imagery.

* Or also, I see piojo is slang in the Andes for "gambling den" -- so maybe the nickname means something like "Dive".

I wonder a lot about how much weight I should give to cognates, to preferring English words which sound like the Spanish term they are translating, where it is feasible. This may end up statistically twisting the meaning of the text a bit as I read it. A similar caveat applies to the matter of using Spanish words in the translated text, this may need to change in a later draft... ("ganchito" in particular is a cheat; and I'm fairly sure the "look away from his footprints" passage is a mistranslation, that I don't understand the sentence as written.)

↻...done

posted evening of November 25th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Mistranslation

| Previous posts about Hernán Rivera Letelier

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |

The genius of Rivera Letelier's Art of Resurrection does not lie in the writing of the plot or the character development. There are events narrated that in aggregate form a plot, to be sure, and it's not (with sufficient suspension of disbelief) a bad plot, but not (by itself) a masterpiece either. The characters are pretty static (except for the two main characters -- and in their cases "development" consists largely of flashbacks sketching out their life stories, more to give context to the narrated events than as part of the main story) -- indeed one could say that in the narrated moment, the characters are almost wooden.

The genius of Rivera Letelier's Art of Resurrection does not lie in the writing of the plot or the character development. There are events narrated that in aggregate form a plot, to be sure, and it's not (with sufficient suspension of disbelief) a bad plot, but not (by itself) a masterpiece either. The characters are pretty static (except for the two main characters -- and in their cases "development" consists largely of flashbacks sketching out their life stories, more to give context to the narrated events than as part of the main story) -- indeed one could say that in the narrated moment, the characters are almost wooden.

settle into their quarters at the Escuela Santa MarÃa* to wait for the mining companies' response to their demands:

settle into their quarters at the Escuela Santa MarÃa* to wait for the mining companies' response to their demands:

de mi propio deshonor

de mi propio deshonor