|

|

Tuesday, June 8th, 2010

Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story "The Dinosaur"* -- today I discover that Monterroso had an august predecessor in Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's story "Baby Shoes" is only six words long, and has inspired a whole genre of six-word micro-stories. Perpetual Folly reprints a Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story "The Dinosaur"* -- today I discover that Monterroso had an august predecessor in Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's story "Baby Shoes" is only six words long, and has inspired a whole genre of six-word micro-stories. Perpetual Folly reprints a  BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with 92 six-word stories from science-fiction or science-fictiony authors including Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, Bruce Sterling, and more. And Pete Berg maintains a blog at sixwordstories.net dedicated to publishing readers' six-word stories. BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with 92 six-word stories from science-fiction or science-fictiony authors including Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, Bruce Sterling, and more. And Pete Berg maintains a blog at sixwordstories.net dedicated to publishing readers' six-word stories.

* (Follow the link! Nick Boalch is attempting to translate "The Dinosaur" into a comic -- what a great idea.)

posted evening of June 8th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Augusto Monterroso

|  |

|

Last November, Harry Kreisler of UC Berkeley's Institute for International Studies interviewed Orhan Pamuk about his new novel and about the novel's relationship with history:

(via ebookforall.com)

posted morning of June 8th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Museum of Innocence

|  |

Monday, June 7th, 2010

Start your week off right: some hypnotic animation loops from Diana Magallón, at The New Post-Literate:

Update: Ooh, and butterflies! (via The Wooster Collective)

posted morning of June 7th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Pretty Pictures

|  |

Sunday, June 6th, 2010

The denizens of the Library have different ways of dealing with their lot in life...

|

Es verosÃmil que esos graves misterios puedan explicarse en palabras: si no basta el lenguaje de los filósofos, la multiforme Biblioteca habrá producido el idioma inaudito que se requiere y los vocabularios y gramáticas de ese idioma. Hace ya cuatro siglos que los hombres fatigan los hexágonos... Hay buscadores oficiales, inquisidores. Yo los he visto en el desempeño de su función: llegan siempre rendidos; hablan de una escalera sin peldaños que casi los mató; hablan de galerÃas y de escaleras con el bibliotecario; alguna vez, toman el libro más cercano y lo hojean, en busca de palabras infames. Visiblemente, nadie espera descubrir nada.

A la desaforada esperanza, sucedió, como es natural, una depresión excesiva. La certidumbre de que algún anaquel en algún hexágono encerraba libros preciosos y de que esos libros preciosos eran inaccesibles, pareció casi intolerable. Una secta blasfema sugirió que cesaran las buscas y que todos los hombres barajaran letras y sÃmbolos, hasta construir, mediante un improbable don del azar, esos libros canónicos. Las autoridades se vieron obligadas a promulgar órdenes severas. La secta desapareció, pero en mi niñez he visto hombres viejos que largamente se ocultaban en las letrinas, con unos discos de metal en un cubilete prohibido, y débilmente remedaban el divino desorden.

Otros, inversamente, creyeron que lo primordial era eliminar las obras inútiles. InvadÃan los hexágonos, exhibÃan credenciales no siempre falsas, hojeaban con fastidio un volumen y condenaban anaqueles enteros: a su furor higiénico, ascético, se debe la insensata perdición de millones de libros. Su nombre es execrado, pero quienes deploran los «tesoros» que su frenesà destruyó, negligen dos hechos notorios. Uno: la Biblioteca es tan enorme que toda reducción de origen humano resulta infinitesimal. Otro: cada ejemplar es único, irreemplazable, pero (como la Biblioteca es total) hay siempre varios centenares de miles de facsÃmiles imperfectos: de obras que no difieren sino por una letra o por una coma. | |

It seems likely that these mysteries could eventually be explained with words: if the philosophers' language be insufficient, our multifarious Library has somewhere produced the never-heard language that will do it, the vocabulary and syntax of this idiom. Four hundred years ago already, men were becoming tired of these hexagonal cells... Now there are official sheriffs, inquisitors. I've seen them myself, carrying out their duties: always visibly exhausted -- they speak of a staircase missing a rung, which they almost died on; they speak of the galleries and the staircases with some librarian; sometimes, they grab the closest book and leaf through it, looking for forbidden words. It's plain on its face that none of them expects to find anything.

On these wild hopes followed, as is natural, a bleak sense of depression. The certainty that some one shelf in some hexagon bears precious books, that these precious books are unreachable, was almost intolerable. One heretic sect proclaimed that we must stop our searches; that all humanity must mix letters and symbols, until we devise -- through some incredible stroke of fortune -- the books of canon. The authorities found themselves obliged to enforce a strict prohibition. The sect vanished, but in my childhood still, I saw old men who would hide themselves in the water closets with some metallic discs and a forbidden cup, and weakly they would imitate divine chaos.

On the other hand were those who believed that man's destiny was to eliminate the nonsensical works. They would attack the hexagons, show (not always forged) credentials, would leaf annoyed through one volume and condemb entire shelves: to their hygienic, ascetic fury is due the senseless loss of millions of books. Their memory is execrated -- but those who deplore the "treasures" that they destroyed in their frenzy are ignoring two important facts. One: the Library is so vast as to be only infinitesimally affected by any reduction of human origin. And the other: every volume is unique, irreplaceable; but (since the Library is everything) there are always hundreds of thousands of imperfect copies: works which differ in only one letter, one comma.

|

Whew! I sat down to copy a sentence from "The Library of Babel" -- the thing about weakly imitating divine chaos -- and kept seeing other things that needed to go into the post... This story comes close to the end of Borges' first proper collection of fictions, The Garden of Forking Paths, and it crystallizes in new ways some of the themes that have been running through this book -- principally it is a logical extension of "The Immortal," with infinite chaos taking the place of eternal life. The narrator's weariness with trying to understand this infinity is palpable. (The old men weakly imitating divine chaos have me flashing on Homer's asemic writing in that story.) It's funny because I went into today's reading with a memory of this as being one of the weakest stories in this volume, and got knocked over by its power.Anyway -- an overlong post with a too-high excerpting-to-analysis ratio, enjoy...

posted evening of June 6th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Ficciones

|  |

It wasn't for nothing, Bertha said. Like the hymns of the next world.

She looked back at Forrest, lying straight out like a dead man, then fixed Jack with her eyes. In heaven, she says, the afterlife, they'll be singing about this world. That's what my grandfather says. All the stories, all of our lives, will be sung like hymns. That's how we'll remember them. That's why it all means something. The problem is that we have to live in this world first, we have to bear it.

The Wettest County in the World is a hugely disturbing book, one that will affect all of your thoughts when you are reading it -- the extremely bleak, violent worldview of the Bondurant brothers gave me pause, made it difficult to think about anything else. But mixed in with that you have some deeply affecting moments of beauty like this one.

(Later:) The radio tune wavered in the light wind and for a moment became clear and Jack found it. Bertha played it often at home on the banjolin, singing softly to his son, her voice as true as Sarah Carter's:

The storms are on the ocean

The heavens may cease to be.

This world may lose its motion, love

If I prove false to thee Jack's relationship with music is almost the central humanizing feature of the book, the thing that lets me relate to him as a human rather than a monster. (For Forrest, it is probably the figures that his grandfather carved, comparatively weak tea...)

posted evening of June 6th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Wettest County in the World

|  |

Saturday, June 5th, 2010

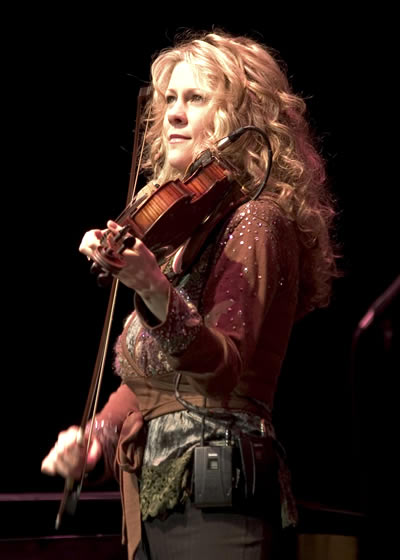

| A mix with some of my favorite fiddle music, and a couple of my own performances... link and notes below the fold. |  |

↷read the rest...

posted evening of June 5th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Fiddling

|  |

As Jack stood there the sounds began to separate in his mind; he felt that he could pick out and listen to each individual mote of sound -- the voices calling out a cadence, the whining violin, the creaking floorboards -- he was able to listen to each thing individually and it seemed to him that this was the second time he had heard such a thing, the first coming at the Dunkard Love Feast. Jack felt that what he was experiencing was somehow part of something hidden, the spare realm of musicians; is this what Bertha heard when she played her mandolin? Rather than a catalog of sounds it sounded to him like the very construction of music, a powerful and beautiful feeling, like manipulating the basic elements of the world.

(Chapter 20, at Little Bean Deshazo's wake)

It is becoming clear in the second half of The Wettest County in the World, that the music in the story is not just there for mood and setting; that it influences the course of events and Jack's perception of the events in some mystical, hard-to-understand way. I wonder if this is going to be clarified at all -- especially Jack's auditory hallucinations at the Dunkard Love Feast seem too important and too specific to go unexplained.

posted afternoon of June 5th, 2010: 1 response

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Thursday, June third, 2010

This picture (via The Wooster Collective) of a wheatpasted painting by Yz in Paris, is about the most soothing, beautiful image I can imagine right now: You can follow Yz's progress at her Facebook page, Vous Êtes Ici.

posted evening of June third, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Graffiti

|  |

|

In the spring Jack Bondurant saw Bertha Minnix playing the mandolin for the first time at a corn shucking at the Mitchell place in Snow Creek. She held her head cocked low, eyes concentrating on the frets of her mandolin, made in the old teardrop style, the rounded bell of the instrument like a wooden scoop nestled against her narrow waist, the tight lace Dunkard bonnet on her crown and the long black dress to the wrist and ankle.... Jack watched Bertha Minnix's fingers ply the strings, the fret hand moving in quick jumps, her plucking a blur of twitching knuckle strokes, working through "Billy in the New Ground" while people slapped their hands in time....Bertha Minnix set her mouth again, cradling the mandolin to her belly, picking out the chords for "Old Dan Tucker," and the younger men and women standing there swayed and sang along. Get out'a th' way for old Dan Tucker

He's too late t' get his supper

Supper is over an' breakfast fry'n

Old Dan Tucker stand'n there cry'n

Washed his face in the fry'n pan

Combed his head on a wagon wheel

An' died with a toothache in his heel

John loaned me Matt Bondurant's excellent novel about his ancestors in Virginia's Franklin County, The Wettest County in the World as Sherwood Anderson called it, and I'm drinking it in -- mixes very nice with the bottle of bourbon John gave me for my birthday. One thing that's really striking me is the quantity and variety of music in the story, and how strongly it affects my reading and the images of the story in my head. The musical styles represented -- old-time, gospel, popular music from the 30's -- are pretty firmly part of my personal soundtrack.Here are Clarke Buehling and the Skirtlifters performing "Old Dan Tucker" at the Beavers Bend Folk Festival last fall:

posted evening of June third, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Music

|  |

Tuesday, June first, 2010

The ending of "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" finds Borges sitting in the hotel in Adrogué where his family spent their summers during his childhood, working on revisions to "an uncertain Quevedian translation... of Browne's Urn Burial."  (What is "Quevedian"? -- It must mean "in the manner of Quevedo" -- I have no idea what this would mean in this context...✱) (What is "Quevedian"? -- It must mean "in the manner of Quevedo" -- I have no idea what this would mean in this context...✱) Sir Thomas Browne's Urn Burial is a 17th-Century discourse on an archæological discovery, a Roman grave site in Norfolk. The text of Hydriotaphia is online at the University of Chicago's Sir Thomas Browne page, with this amusing note from the maintainer of the site: Hydriotaphia and the Garden of Cyrus were published together in 1658, on which edition this web edition is based. They form a work that is somewhat difficult but rewarding to read. The number of critics who have a rock-solid grasp of the entire work can be counted on the fingers of one foot, so there's an open field out there for those inclined towards such work. Most critics read Hydriotaphia and comment on it as though they had in fact finished both sides. Among those whose comments are more interesting are Carlyle, Lytton Strachey, and, somewhat surprisingly, Virginia Woolf. Among those whose work seems to be based on something else the stand-out is Gosse✽, whose commentary is so unrelated to the text putatively in front of him that it becomes a case-study in itself.

William Hamilton's address "Sir Thomas Browne, Jorge Luis Borges y Yo" is reprinted in the Atlantic of June 2003. Borges refers to his translation of Browne's Urne Buriall in this interview. It seems like he did actually translate it or part of it in Quevedian Spanish, I am looking for more info about this. Christopher Johnson has an essay in Translation and Literature called "Intertextuality and Translation: Borges, Browne, and Quevedo".

✱Possibly "Quevedian" just means the language of the translation is archaic, 17th-Century Spanish. -- More info from John and Rick in comments. ✽And Gosse père wrote Omphalos, which prefigures Russell's idea that the world was created just minutes ago with people's memories created intact, which is referenced in a footnote to "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" -- bringing us full circle.

posted evening of June first, 2010: 5 responses

➳ More posts about Jorge Luis Borges

| Previous posts

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |