|

|

Wednesday, June 9th, 2010

The piece of Pliny's Natural History which Funes is reciting the third time Borges sees him is from the beginning of Book VII*, chapter 26; in Philemon Holland's translation: AS TOUCHING MEMORIE, the greateſt gift of Nature, and moſt neceſſarie of all others for this life; hard it is to judge and ſay who of all others deſerved the cheefe honour therein: conſidering how many men have excelled, and woon much glorie in that behalfe. King Cyrus was able to call every ſouldior that he had through his whole armie, by his owne name. L. Scipio could doe the like by all the citizens of Rome. Semblably, Cineas, Embaſſador of king Pyrrhus, the very next day that he came to Rome, both knew and alſo ſaluted by name all the Senate, and the whole degrees of Gentlemen and Cavallerie in the cittie. Mithridates the king, reigned over two and twentie nations of diverſe languages, and in ſo many tongues gave lawes and miniſtred juſtice unto them, without truchman: and when hee was to make ſpeech unto them in publicke aſſemblie reſpectively to every nation, he did performe it in their owne tongue, without interpretor. One Charmidas or Carmadas, a Grecian,†††was of ſo ſingular a memorie, that he was able to deliver by heart the contents word for word of all the bookes that a man would call for out of any librarie, as if he read the ſame preſently within a booke. At length the practiſe hereof was reduced into an art of Memorie: deviſed and invented firſt by Simonides Melicus, and afterwards brought to perfection and conſummate by Metrodorus Scepſius: by which a man might learne to rehearſe againe the ſame words of any diſcourſe whatſoever, after once hearing.

†††Carneades, according to Cicero and Quintilian.

* (The same volume to which John of Pannonia will refer in "The Theologians".)

posted evening of June 9th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Ficciones

|  |

|

My sorry condition of being an Argentine prevents me from engaging in the genre -- obligatory in Uruguay -- of dithyramb; my subject is after all a Uruguayan.

Line from "Funes, the memorious" has me looking around to see if there are any examples of old Uruguayan dithyramb chanting... and I do not find that, not exactly*. But check out this more recent Chilean group, Ditirambo.

* And I have a sneaking hunch that Borges is not saying quite what I at first took him to be saying, either -- that the usage is exaggeration or mis-naming, that "dithyramb" is here just a manner of speaking.

posted evening of June 9th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Jorge Luis Borges

|  |

|

An idea I just had which I think it would be fun to implement: a database table with favorite (striking or profound) brief lines from each book I read -- When you read the archive page for the book in question, those lines, or some randomized subset of them, would be displayed as part of the information in the left hand sidebar. Add to this a setting in the database for "current reading", the book or books that I'm currently reading/thinking about, and a set of lines from those books could be on the front page's sidebar. A little bit like the epigraphs I run at the top of the page, but a bit more fleeting, less a permanent part of the site. For instance I really liked the line, "He does not know -- nobody could know -- my immeasurable contrition, my weariness," from "The Garden of Forking Paths." But it really only seems meaningful in the context of that reading. (This would really free me up in terms of posting short quotations, too -- generally I try only to post a quotation when I have something in particular to say about it. And only to create a new epigraph when I find a really meaningful one. -- So this is a third way.)

Two notes about the translation of that line, * Thanks John for helping with the adjective, "immeasurable" sounds much better than "innumerable" or than "endless", and * Thanks Dr. Hurley for the repetition of "my" at the end, I was leaning towards just using "contrition and weariness" as being the closest thing in format to "contrición y cansancio" -- but somehow that doesn't sound quite right in English.

Implementation: have a button or link on the editing view of the blog that is called "Add Quotation" or something similar -- clicking on it will bring up a dialog box or form where you can enter your quote and the book it is from -- then the the "current reading" books will be books for which I have either posted a quotation or a journal entry over the past say week or two.

posted evening of June 9th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about The site

|  |

Tuesday, June 8th, 2010

The caprice, the fantasy, the utopia of a Total Library has certain characteristics which are easily mistaken for virtues. Incredible, in the first place, how long it took mankind to arrive at this idea. Certain passages which Aristotle attributes to Democritus and to Leucippus clearly prefigure it; but its tardy inventor is Gustav Theodor Fechner; its first expositor, Kurd Lasswitz.

The note in Sur #59 to which Borges referred in the foreword to The Garden of Forking Paths, is his essay "The Total Library" -- I thank Daniel Balderston of the Borges Center at U. Pittsburgh for pointing this out to me. "The Total Library" (which has appeared many times in translation, most recently in Selected Non-Fictions) is a lovely read and excellent companion material for "The Library of Babel" -- it lacks the haunting, overpowering sense of futility which is that story's strongest characteristic, but it lays out clearly and concisely the premises underlying the story and its sources of inspiration.

See also Theodor Pavlapoulos' essay, Lasswitz and Borges: Indexing the Library of Everything; and Lasswitz' story Die Universalbibliothek.

posted evening of June 8th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

|

Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story "The Dinosaur"* -- today I discover that Monterroso had an august predecessor in Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's story "Baby Shoes" is only six words long, and has inspired a whole genre of six-word micro-stories. Perpetual Folly reprints a Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story "The Dinosaur"* -- today I discover that Monterroso had an august predecessor in Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's story "Baby Shoes" is only six words long, and has inspired a whole genre of six-word micro-stories. Perpetual Folly reprints a  BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with 92 six-word stories from science-fiction or science-fictiony authors including Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, Bruce Sterling, and more. And Pete Berg maintains a blog at sixwordstories.net dedicated to publishing readers' six-word stories. BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with 92 six-word stories from science-fiction or science-fictiony authors including Frank Miller, Neil Gaiman, Bruce Sterling, and more. And Pete Berg maintains a blog at sixwordstories.net dedicated to publishing readers' six-word stories.

* (Follow the link! Nick Boalch is attempting to translate "The Dinosaur" into a comic -- what a great idea.)

posted evening of June 8th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Augusto Monterroso

|  |

|

Last November, Harry Kreisler of UC Berkeley's Institute for International Studies interviewed Orhan Pamuk about his new novel and about the novel's relationship with history:

(via ebookforall.com)

posted morning of June 8th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Museum of Innocence

|  |

Monday, June 7th, 2010

Start your week off right: some hypnotic animation loops from Diana Magallón, at The New Post-Literate:

Update: Ooh, and butterflies! (via The Wooster Collective)

posted morning of June 7th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Pretty Pictures

|  |

Sunday, June 6th, 2010

The denizens of the Library have different ways of dealing with their lot in life...

|

Es verosÃmil que esos graves misterios puedan explicarse en palabras: si no basta el lenguaje de los filósofos, la multiforme Biblioteca habrá producido el idioma inaudito que se requiere y los vocabularios y gramáticas de ese idioma. Hace ya cuatro siglos que los hombres fatigan los hexágonos... Hay buscadores oficiales, inquisidores. Yo los he visto en el desempeño de su función: llegan siempre rendidos; hablan de una escalera sin peldaños que casi los mató; hablan de galerÃas y de escaleras con el bibliotecario; alguna vez, toman el libro más cercano y lo hojean, en busca de palabras infames. Visiblemente, nadie espera descubrir nada.

A la desaforada esperanza, sucedió, como es natural, una depresión excesiva. La certidumbre de que algún anaquel en algún hexágono encerraba libros preciosos y de que esos libros preciosos eran inaccesibles, pareció casi intolerable. Una secta blasfema sugirió que cesaran las buscas y que todos los hombres barajaran letras y sÃmbolos, hasta construir, mediante un improbable don del azar, esos libros canónicos. Las autoridades se vieron obligadas a promulgar órdenes severas. La secta desapareció, pero en mi niñez he visto hombres viejos que largamente se ocultaban en las letrinas, con unos discos de metal en un cubilete prohibido, y débilmente remedaban el divino desorden.

Otros, inversamente, creyeron que lo primordial era eliminar las obras inútiles. InvadÃan los hexágonos, exhibÃan credenciales no siempre falsas, hojeaban con fastidio un volumen y condenaban anaqueles enteros: a su furor higiénico, ascético, se debe la insensata perdición de millones de libros. Su nombre es execrado, pero quienes deploran los «tesoros» que su frenesà destruyó, negligen dos hechos notorios. Uno: la Biblioteca es tan enorme que toda reducción de origen humano resulta infinitesimal. Otro: cada ejemplar es único, irreemplazable, pero (como la Biblioteca es total) hay siempre varios centenares de miles de facsÃmiles imperfectos: de obras que no difieren sino por una letra o por una coma. | |

It seems likely that these mysteries could eventually be explained with words: if the philosophers' language be insufficient, our multifarious Library has somewhere produced the never-heard language that will do it, the vocabulary and syntax of this idiom. Four hundred years ago already, men were becoming tired of these hexagonal cells... Now there are official sheriffs, inquisitors. I've seen them myself, carrying out their duties: always visibly exhausted -- they speak of a staircase missing a rung, which they almost died on; they speak of the galleries and the staircases with some librarian; sometimes, they grab the closest book and leaf through it, looking for forbidden words. It's plain on its face that none of them expects to find anything.

On these wild hopes followed, as is natural, a bleak sense of depression. The certainty that some one shelf in some hexagon bears precious books, that these precious books are unreachable, was almost intolerable. One heretic sect proclaimed that we must stop our searches; that all humanity must mix letters and symbols, until we devise -- through some incredible stroke of fortune -- the books of canon. The authorities found themselves obliged to enforce a strict prohibition. The sect vanished, but in my childhood still, I saw old men who would hide themselves in the water closets with some metallic discs and a forbidden cup, and weakly they would imitate divine chaos.

On the other hand were those who believed that man's destiny was to eliminate the nonsensical works. They would attack the hexagons, show (not always forged) credentials, would leaf annoyed through one volume and condemb entire shelves: to their hygienic, ascetic fury is due the senseless loss of millions of books. Their memory is execrated -- but those who deplore the "treasures" that they destroyed in their frenzy are ignoring two important facts. One: the Library is so vast as to be only infinitesimally affected by any reduction of human origin. And the other: every volume is unique, irreplaceable; but (since the Library is everything) there are always hundreds of thousands of imperfect copies: works which differ in only one letter, one comma.

|

Whew! I sat down to copy a sentence from "The Library of Babel" -- the thing about weakly imitating divine chaos -- and kept seeing other things that needed to go into the post... This story comes close to the end of Borges' first proper collection of fictions, The Garden of Forking Paths, and it crystallizes in new ways some of the themes that have been running through this book -- principally it is a logical extension of "The Immortal," with infinite chaos taking the place of eternal life. The narrator's weariness with trying to understand this infinity is palpable. (The old men weakly imitating divine chaos have me flashing on Homer's asemic writing in that story.) It's funny because I went into today's reading with a memory of this as being one of the weakest stories in this volume, and got knocked over by its power.Anyway -- an overlong post with a too-high excerpting-to-analysis ratio, enjoy...

posted evening of June 6th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Logograms

|  |

It wasn't for nothing, Bertha said. Like the hymns of the next world.

She looked back at Forrest, lying straight out like a dead man, then fixed Jack with her eyes. In heaven, she says, the afterlife, they'll be singing about this world. That's what my grandfather says. All the stories, all of our lives, will be sung like hymns. That's how we'll remember them. That's why it all means something. The problem is that we have to live in this world first, we have to bear it.

The Wettest County in the World is a hugely disturbing book, one that will affect all of your thoughts when you are reading it -- the extremely bleak, violent worldview of the Bondurant brothers gave me pause, made it difficult to think about anything else. But mixed in with that you have some deeply affecting moments of beauty like this one.

(Later:) The radio tune wavered in the light wind and for a moment became clear and Jack found it. Bertha played it often at home on the banjolin, singing softly to his son, her voice as true as Sarah Carter's:

The storms are on the ocean

The heavens may cease to be.

This world may lose its motion, love

If I prove false to thee Jack's relationship with music is almost the central humanizing feature of the book, the thing that lets me relate to him as a human rather than a monster. (For Forrest, it is probably the figures that his grandfather carved, comparatively weak tea...)

posted evening of June 6th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Wettest County in the World

|  |

Saturday, June 5th, 2010

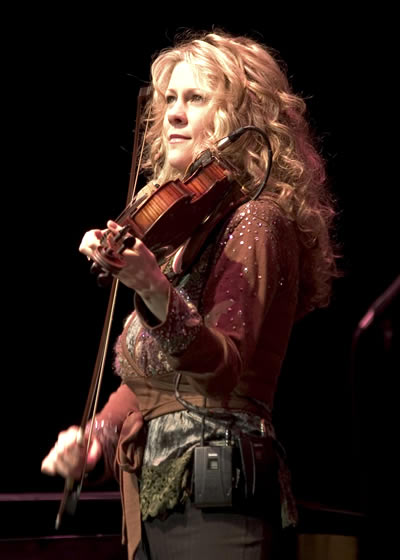

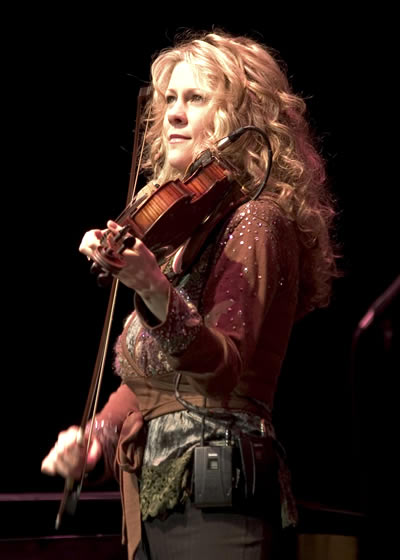

| A mix with some of my favorite fiddle music, and a couple of my own performances... link and notes below the fold. |  |

↷read the rest...

posted evening of June 5th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Fiddling

| Previous posts

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |

Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story

Longtime readers will remember how excited I was to read Augusto Monterroso's short story  BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with

BlackBook feature in which 25 major writers -- skewing older-white-male-mid-century -- contributed their six-worders; I'm partial to Brian Bouldrey's contribution, but there is a lot to be said for Norman Mailer's, too. Wired Magazine ran a feature with