|

|

Monday, March 22nd, 2010

"The Theologians" offers an alternate vision of eternity: Months later, when the Council of Pergamo was convened, the theologian entrusted with refuting the errors of the Monotoni was (predictably) John of Pannonia; his learnèd, measured refutation was the argument that condemned the heresiarch Euphorbus to the stake. This has occured once, and will occur again, said Euphorbus. It is not one pyre you are lighting, it is a labyrinth of fire. If all the fires on which I have been burned were brought together here, the earth would be too small for them, and the angels would be blinded. These words I have spoken many times. Then he screamed, for the flames had engulfed him. It is (perhaps) not immediately obvious that eternal recurrence entails the same extension of the present moment I discussed in my last post -- it was not immediately obvious to me. But if the present moment is going to be repeated an infinite number of times, it must have eternal duration. And indeed you can visualize the universe of eternal recurrence with the same four-dimensional model; but instead of a straight vector, the 3-space which we inhabit has to follow a cyclical orbit. I found the end of "The Theologians" confusing: The end of the story can only be told in metaphors, since it takes place in the kingdom of heaven, where time does not exist.* One might say that Aurelian spoke with God and found that God takes so little interest in religious differences that He took him for John of Pannonia. That, however, would be to impute confusion to the divine intelligence. It is more correct to say that in paradise, Aurelian discovered that in the eyes of the unfathomable deity, he and John of Pannonia (the orthodox and the heretic, the abominator and the abominated, the accuser and the victim) were a single person. -- I would have thought the pairing of "orthodox and heretic" would apply, in the context of this story, to Aurelian (or John of Pannonia) in counterpoint to Euphorbus -- that the two churchmen were colleagues with maybe a small rivalry, but both in good graces with the Church. I am missing something here.

* (And what a marvelous, breathtaking statement this is.)

Update:... on rereading I see that I was giving far too little weight to the rivalry between Aurelian and Pannonia -- this is really the principal subject of the story.

posted evening of March 22nd, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Aleph

|  |

(The president's address to the House Democratic Caucus is worth while.)

posted evening of March 22nd, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Politics

|  |

Sunday, March 21st, 2010

Listen:Billy Pilgrim has come unstuck in time. Billy has gone to sleep a senile widower and awakened on his wedding day. He has walked through a door in 1955 and come out another one in 1941. He has gone back through that door to find himself in 1963. He has seen his birth and his death many times, he says, and paid random visits to all the events in between. He says. Slaughterhouse-5: or, The Children's Crusade

In Appendix III to his Christelige Dogmatik, Erfjord rebuts this passage [i.e., Runeberg's claim that it would be blasphemous to limit the Messiah's suffering to "the agony of one afternoon on the cross."] He notes that the crucifixion of God has not ended, because that which happened once in time is repeated endlessly in eternity. Judas, now, continues to hold out his hand for the silver, continues to kiss Jesus' cheek, continues to scatter the pieces of silver in the temple, continues to knot the noose on the field of blood. (In order to justify this statement, Erfjord cites the last chapter of the first volume of Jaromir HladÃk's Vindication of Eternity.)"Three Versions of Judas"

Listen: I want to take advantage of your interest in my blog, to post about some thoughts I spent a good deal of time on thinking about in my first year of college, these 21 years back -- when I was in the throes of what Scott would term my "Vonnegut phase."* This post will probably be rambling and pointless (ill-informed, too!), so if those qualities turn you off, just stop reading now, and I will (try to) stop apologizing now.

In my first year of college I spent a lot of time thinking about physics. One thing that particularly got my attention was the idea of time as a fourth dimension. My understanding of this (and listen, I never got very far with physics) was that the universe could be visualized as a four-dimensional space containing everything that ever happened or will happen, and the three-dimensional universe we inhabit as a three-dimensional space moving through this hyper-space at a constant rate -- this motion is what we experience as "time," and the present moment is the intersection of our 3-space with Reality. (I think this idea may have been laid out more fully in Edwin Abbot's Flatland.**) This picture of physical reality, which is Erfjord's conception of reality in the footnote to "Three Versions of Judas" -- taken in combination with an idealism that sees thought as existing separately from physical reality -- makes possible the chrono-synclastic infundibulum; Billy Pilgrim's experience takes as read that our "present moment" is something which has extended, eternal existence.

Well: I got upset about this. It became very important to me, to show that 3 physical dimensions are all there is -- that motion is reality, not an illusion. (I still can't answer the question, Well, what would be the difference anyway?) That past and future have existence only in our memories and expectations -- that the fourth axis is a convenient way of representing motion, nothing more. What does this entail? There is a danger of solipsism in this view -- since every perception of mine is a perception of something that has happened, and every communication reaches its object after it is uttered, saying that only the present moment "really exists" can be a way of saying that only my consciousness really exists -- and we're back to idealism. I worked through that, and my solution was materialistic -- consciousness is an epiphenomenon of the material objects that exist, that are moving -- but it never got very coherent given my lack of philosophical chops.

So there you have it, for a long time now I've been walking around with this vision of eternity, but never really committed it to paper or (since freshman year) even talked about it much, since it seemed kind of silly and pointless. It's brought back to mind by the Borges reading I've been doing recently, I thought I might as well write it down.

* ("Phase"? Well it's true, I read his books way more frequently and obsessively two decades ago than I do now; OTOH I have repeatedly been surprised, going back to them, at how well they have held up, at how strongly they continue to engage me. Though I see looking back through my blog, I have not written much at all about them.) ** (Or thinking further, this imagery might actually have been in Slaughterhouse-5.)

posted evening of March 21st, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Ficciones

|  |

|

Riding your bike uphill is, properly considered, a meditative activity. On a long incline, one is (well, "I am") moving slowly enough that one doesn't need to pay as much attention to the roadway and traffic as one does on a downhill or level stretch. As I was riding up South Mountain this morning -- a particularly brutal hill, it takes me more than 5 minutes, maybe closer to ten -- it occurred to me that if I could get the internal DJ (who this morning was spinning a bizarre mix of "Ripped off and promoted lame" by the Pop-o-pies and Bach's Double Concerto) and the internal Narrator (who was busy composing this very blog post...) to  quiet down, it would be a good opportunity for introspection. quiet down, it would be a good opportunity for introspection. Ellen's suggestion this morning that we drive up to the park on top of the mountain and go for a walk made me think what a nice day it was for a bike ride, and I ought to ride up and meet Ellen and Sylvia (and Pixie) -- this turned into a long, peripatetic bike ride for me, Google Maps tells me I rode 16 miles in all, with the midpoint of the ride being meeting the rest of the family for a walk in the park. A really nice time (though those uphills made me wish I weighed a little less.)

posted morning of March 21st, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Cycling

|  |

Saturday, March 20th, 2010

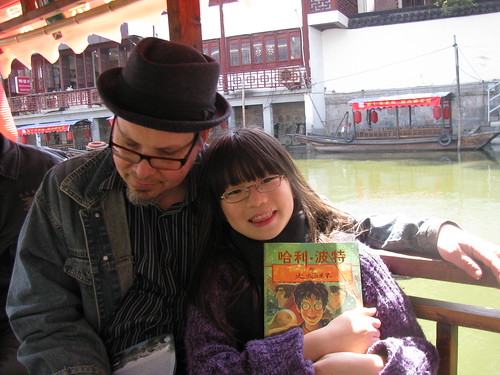

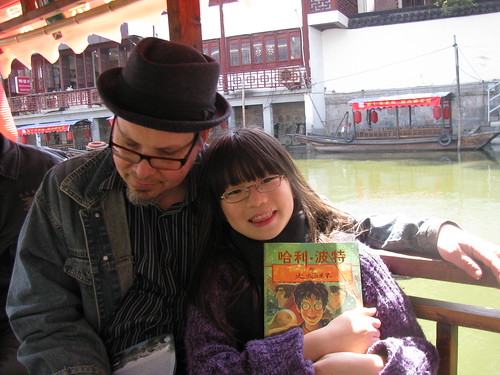

Here we are, sitting on the porch on this divinely pleasant first day of Spring: Have a happy equinox, everyone! Thanks for snapping our photo, Michele!

posted evening of March 20th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about the Family Album

|  |

That day, all was revealed to me. The Troglodytes were the Immortals; the stream and its sand-laden waters, the River sought by the rider. As for the city whose renown had spread to the very Ganges, the Immortals had destroyed it almost nine hundred years ago. Out of the shattered remains of the City's ruin they had built on the same spot the incoherent city I had wandered through -- that parody  or antithesis of the City which was also a temple to the irrational gods that rule the world and to those gods about whom we know nothing save that they do not resemble man. The founding of this city was the last symbol to which the Immortals had descended; it marks the point at which, esteeming all exertion vain, they resolved to live in thought, in pure speculation. They built that carapace, abandoned it, and went off to make their dwellings in the caves. or antithesis of the City which was also a temple to the irrational gods that rule the world and to those gods about whom we know nothing save that they do not resemble man. The founding of this city was the last symbol to which the Immortals had descended; it marks the point at which, esteeming all exertion vain, they resolved to live in thought, in pure speculation. They built that carapace, abandoned it, and went off to make their dwellings in the caves.

I know the parallels are pretty vague; but this portion of "The Immortal" is reminding me of nothing so much as the City of Reality (and Illusions), in The Phantom Tollbooth.

posted evening of March 20th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Jorge Luis Borges

|  |

|

Reading both "The Secret Miracle" and "Three Versions of Judas" -- I am identifying strongly with the main characters (HladÃk and Runeberg) -- but instead of identifying with the narrator, I am identifying the narrator as Borges -- the "position of the reader" in which I find myself,  is listening to him telling a story. (This reminds me of how much I enjoyed reading his lectures, picturing him addressing the class.) The third person works very well here. is listening to him telling a story. (This reminds me of how much I enjoyed reading his lectures, picturing him addressing the class.) The third person works very well here. These two stories go together very well, and are moderately distinct from the rest of the fictions -- both are strongly dependent on religious content*; both narrate the composition of a work which vindicates the main character -- HladÃk's "grand invisible labyrinth," Runeberg's heresy -- and the character's death. "The Secret Miracle" seems to me the closest in style to Poe of any of Borges' fictions.

*I was going to call them "deeply religious," but I don't think that's quite right -- Runeberg is "deeply religious," HladÃk's experience is one of religious ecstasy; understanding each story requires a willingness to identify with religious sentiment but not, I think, any personal commitment to religious thinking. I have always assumed Borges was an atheist (and a lapsed Catholic) but I don't know if that is accurate.

posted morning of March 20th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Friday, March 19th, 2010

Hladik's first emotion was simple terror. He reflected that he wouldn't have quailed at being hanged, or decapitated, or having his throat slit, but being shot by a firing squad was unbearable. In vain he told himself a thousand times that the pure and universal act of dying was what ought to strike fear, not the concrete circumstances of it, and yet Hladik never wearied of picturing to himself those circumstances.

"The Secret Miracle"

posted evening of March 19th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Collected Fictions

|  |

Thursday, March 18th, 2010

At the beginning of every episode of Heimat: eine deutsche Chronik, before the titles (every episode so far, excluding the first -- I'm watching the fifth now) there is a short piece of narration in English while the camera pans over a set of old photographs of the characters in Schabbach. This was kind of jarring to me at first -- it is not explained, the narrator still has not been identified. The only character who has emigrated to the U.S. is Paul, and the narrator refers to Paul in the third person... Looking at the screenplay I see the narrator identified as Glasisch, who (I believe) is still in Schabbach at the present moment, 1938 or so. This is (assuming I haven't missed some key bit of exposition) a pretty complex piece of plotting -- the viewer knows Glasisch as a character, and knows the narrator as a Schabbacher who has emigrated, but does not know they are the same. Presumably that will be revealed at some point. At the beginning of every episode of Heimat: eine deutsche Chronik, before the titles (every episode so far, excluding the first -- I'm watching the fifth now) there is a short piece of narration in English while the camera pans over a set of old photographs of the characters in Schabbach. This was kind of jarring to me at first -- it is not explained, the narrator still has not been identified. The only character who has emigrated to the U.S. is Paul, and the narrator refers to Paul in the third person... Looking at the screenplay I see the narrator identified as Glasisch, who (I believe) is still in Schabbach at the present moment, 1938 or so. This is (assuming I haven't missed some key bit of exposition) a pretty complex piece of plotting -- the viewer knows Glasisch as a character, and knows the narrator as a Schabbacher who has emigrated, but does not know they are the same. Presumably that will be revealed at some point.

Update: At the beginning of episode 8, the narrator says "The war memorial was unveiled in 1920. I was there -- there I am, that's me!" as he points to a picture of Glasisch.

posted evening of March 18th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Heimat: eine deutsche Chronik

|  |

Wednesday, March 17th, 2010

The metaphysicians of Tlön seek not truth, or even plausibility -- they seek to amaze, astound. In their view, metaphysics is a branch of the literature of fantasy.

What really got my attention in Josipovici's piece Borges and the Plain Sense of Things, was his focus on the postscript to the story, on the narrator's experience of Tlön infiltrating and disintegrating our world. I see now that I have in the past read this story as if it were written by a Tlönian metaphysician, as a work of fantasy: my understanding of the story has been twofold, of Borges asking me to imagine a world where idealism is the obviously correct way to understand reality and a human conspiracy to invent such a world, and of Borges asking me to imagine this invented world overtaking our own. But I've been missing, or not paying enough attention to, a third aspect of this (vast) story, how Borges the narrator feels about this alteration of reality. (Maybe I should have been tipped off by Borges' footnote #2, in which he refers to Russell's idea that the world could have been "created only moments ago, filled with human beings who 'remember' an illusory past." It has never been very clear to me what this note is doing in the story; but it could certainly be there to tie the thought-experiment in to the present moment in history from which Borges is writing.) (Maybe I should have been tipped off by Borges' footnote #2, in which he refers to Russell's idea that the world could have been "created only moments ago, filled with human beings who 'remember' an illusory past." It has never been very clear to me what this note is doing in the story; but it could certainly be there to tie the thought-experiment in to the present moment in history from which Borges is writing.)Speaking of footnotes -- one of the things that is great about this edition of the fictions, is Hurley's painstakingly researched, unobtrusive endnotes. They are easily ignorable when you want to read the story without interruption; and they add a whole lot when you read the story with interruptions. I am taken aback to find that all of the people named in this story (excluding, perhaps, Herbert Ashe) -- Carlos Mastronardi, Néstor Ibarra, Alfonso Reyes, Xul Solar, etc. -- are real figures from Borges' milieu, and very interested at some of the books referenced. And this does not come from Hurley's notes -- but I was very happy to learn that there really is an Anglo-American Cyclopædia from 1917, which really is a reprint of an older edition of Encyclopædia Britannica.

posted evening of March 17th, 2010: Respond

| Previous posts

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |