|

|

Friday, August 31st, 2007

Chapter 29, in which the foul deed is done, is totally gripping. I am starting to wonder (well -- I had been wondering, but this chapter is making it worse) whose name is Red -- I think it might be Black somehow.* The principal reason I'm thinking this is because Enishte Effendi (lovely nickname, I think it means "Mr. Uncle") has his chapters titled, "I am your beloved uncle" -- your beloved uncle, as if he is talking to Black. Just a hunch tho. A few nice things from this chapter: - Enishte and the murderer discussing guilt -- that the artist is motivated in part by "fear of retribution" -- "how the endless guilt both deadens and nourishes the artist's imagination."

- Enishte's compliment to the murderer: "What your pen draws is neither truthful nor frivolous."

- Enishte's final, long speech about the destiny of their art.

- "Just before I died, I actually longed for my death, and at the same time, I understood the answer to the question that I'd spent my entire life pondering, the answer I couldn't find in books: How was it that everybody, without exception, succeeded in dying? It was precisely through this simple desire to pass on. I also understood that death would make me a wiser man."

*Mm, strike that -- I just looked in the table of contents and noticed chapter 31 will be titled, "I am Red". So, apparently Red is a distinct character. That's my assumption at this point anyhow.

posted evening of August 31st, 2007: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Orhan Pamuk

|  |

Saturday, September first, 2007

Ah ok, I got it, not just a distinct character but a distinct type of character -- by my count there are three or four types of narrators so far in this book: {Black, Mr. Uncle, Mr. Elegant, the Murderer, Orhan, Shekure, Esther, and the various miniaturists}; {Dog, Tree, Gold Coin}; and {Red} -- Maybe the Murderer should get a set of his own. Pamuk has impeccable timing. As evidence of this look at the following paragraph, ignoring the minor infelicities of the translation. Red tells how he came to be: Hush and listen to how I developed such a magnificent red tone. A master miniaturist, an expert in paints, furiously pounded the best variety of dried red beetle from the hottest climes of Hindustan into a fine powder using his mortar and pestle. He prepared five drachmas of the red powder, one drachma of soapwort and a half drachma of lotor. He boiled the soapwort in a pot containing three okkas of water. Next, he mixed thoroughly the lotor into the water. He let it boil for as long as it took to drink an excellent cup of coffee. As he enjoyed the coffee, I grew as impatient as a child about to be born. (The paragraph goes on with more description of the mixing and preparation.) The position of the last sentence quoted here is sublime. It makes the description of preparing red dye, which is starting to feel just like reading a recipe, concrete, locating it in time and giving it a personal dimension.Chapter 31 feels very important to me in a similar way to chapter 29 of Snow. It comes about halfway through the book, just after a couple of important plot elements have occurred, and it distances the reader from the immediacy of the narration. And I think we may be seeing the heart of the book in this passage: "What is the meaning of red?" the blind miniaturist who'd drawn the horse from memory asked again."The meaning of color is that it is there before us and we see it," said the other. "Red cannot be explained to he who cannot see." "To deny God's existence, victims of Satan maintain that God is not visible to us," said the blind miniaturist who'd rendered the horse. "Yet, he appears to those who can see," said the other master. "It is for this reason that the Koran states that the blind and the seeing are not equal."

posted afternoon of September first, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Monday, September third, 2007

Al-Ahram Weekly looks like a very useful resource for learning about what's going on in the Islamic world. I am reading an essay about Snow right now, written on the occasion of Pamuk's receiving the Nobel Prize; and a review of My Name is Red.

posted afternoon of September third, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about Snow

|  |

Sunday, September 9th, 2007

Since chapter 31 of My Name is Red I have been feeling a little at odds with Pamuk's desire to advance the plot, which has been seeming to interfere with the lovely character development and aphoristic nature of the first half of the book. With today's reading however, chapters 43 through 47, he is coming back to the narrative style that I have fallen in love with. Chapter 47 ("I, Satan") is especially nice -- it has been too long since we heard from the coffee-house storyteller, whom I am identifying as Pamuk. He (like Pamuk) obviously has a polemical point -- is not impartial -- but his voice is lovely and seductive enough, and I'm close enough to in agreement with his side of the argument, that I am letting my guard down and just basking in his voice. Here's what his Satan has to say about moralizing preachers: I am not the source of all the evil and sin in the world. Many people sin out of their own blind ambition, lust, lack of willpower, baseness, and most often, out of their own idiocy without any instigation, deception or temptation on my part. However absurd the efforts of certain learned mystics to absolve me of any evil might be, so too is the assumption that I am the source of all of it, which also contradicts the Glorious Koran. I'm not the one who tempts every fruit monger who craftily foists rotten apples upon his customers, every child who tells a lie, every fawning sycophant, every old man who has obscene daydreams or every boy who jacks off. Even the Almighty couldn't find anything evil in passing wind or jacking off. Sure, I work very hard so you might commit grave sins. But some hojas claim that all of you who gape, sneeze or even fart are my dupes, which tells me they haven't understood me in the least. Let them misunderstand you, so you can dupe them all the more easily, you might suggest. True. But let me remind you, I have my pride, which is what caused me to fall out with the Almighty in the first place...

posted evening of September 9th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Tuesday, September 11th, 2007

(Well, or tangling them up at least.) I woke up this morning with an image from my dream fully formed. A man about my age is at a family gathering -- the crowd includes his parents, brothers and sisters and their families, and his child or children. Maybe some of his aunts and uncles as well. He is stoned and is scribbling random-seeming lines on a large piece of blank paper as he narrates in a kind of vindictive, complaining way. A few people are listening to him, others are involved in their own conversations. He moves on to something else and his son (perhaps nephew), 4 or 5 years old, starts coloring in the scribbles, eventually coming out with a very nice picture of a scene from the fairy-tale "The Frog King". Thinking about this brought to mind Shekure's observations about dreaming from My Name is Red; and that made me suddenly realize that my insight on Friday about bragging and complaining is exactly parallel to Shekure's thoughts -- with the added clarification that what I was talking about was not "ways of thinking" but "ways of narrating" my thoughts, talking about what I am thinking. And that Shekure was not saying she wouldn't tell a dream; she was just pointing out that the relation would be a lie in fundamental ways.

posted morning of September 11th, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about Dreams

|  |

Friday, September 14th, 2007

They tell a story in Bukhara that dates back to the time of Abdullah Khan. This Uzbek Khan was a suspicious ruler, and though he didn't object to more than one artist's brush contributing to the same illustration, he was opposed to painters copying from one another's pages -- because this made it impossible to determine which of the artists brazenly copying from one another was to blame for an error. More importantly, after a time, instead of pushing themselves to seek out God's memories within the darkness, pilfering miniaturists would lazily seek out whatever they saw over the shoulder of the artist beside them. For this reason, the Uzbek Khan joyously welcomed two great masters, one from Shiraz in the South, the other from Samarkand in the East, who'd fled from war and cruel shahs to the shelter of this court; however, he forbade the two celebrated talents to look at each other's work, and separated them by giving them small workrooms on opposite ends of his palace, as far from each other as possible. Thus, for exactly thirty-seven years and four months, as if listening to a legend, these two great masters each listened to Abdullah Khan recount the magnificence of the other's never-to-be-seen work, how it differed from or was oddly similar to the other's. Meanwhile, they both lived dying of curiosity about each other's paintings. Later still sitting upon either edge of a large cushion, holding each other's books on their laps and looking at the pictures that they recognized from Abdullah Khan's fables, both the miniaturists were overcome with great disappointment because the illustrations they saw weren't nearly as great as those they'd anticipated from the stories they heard, but instead appeared, much like all the pictures they'd seen in recent years, rather ordinary, pale and hazy. The two great masters didn't then realize that the reason for this haziness was the blindness that had begun to descend upon them, nor did they realize it after both had gone completely blind, rather they attributed the haziness to having been duped by the Khan, and hence they died believing dreams were more beautiful than pictures. Chapter 51 seems to me like a huge achievement. It contains the climax of this book's inner story, the one about blindness and perfection, which I think is fully as mesmerizing and befuddling, as bestowing of clarity, as the outer story. I struggle to think of any other writer who can maintain this kind of structure in his tapestries -- Borges comes to mind but was not, after all, a novelist (in the contemporary sense of the word anyway -- and I'm not sure a sense of that word exists which would make it appropriate). Master Osman, who I believe has narrated once before but did not really grab me then, emerges as a powerful, tragic figure. (He is certainly the main character of this inner story.) This chapter marks the first time we are hearing about blindness, its seductive nature, its role in creation, from a character who has been identified throughout as nearing blindness. What could be more exquisite than looking at the world's most beautiful pictures while trying to recollect God's vision of the world?

posted evening of September 14th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Saturday, September 15th, 2007

In his review at the Times Literary Supplement, Dick Davis describes chapter 51 of My Name is Red as "one of the most beguilingly lovely ten pages or so of art history I've ever read," which seems to me very well-put.

posted morning of September 15th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Sunday, September 16th, 2007

Chapter 58: one of this book's longest chapters; a 20-page crescendo. By the last page of the chapter, the volume is nearly deafening, and it suddenly drops off to a whisper. This chapter brings out new complications in the debate the book has been engaged with, between illumination and painting, between absence and presence of the author, between seeing the world from above and looking toward the horizon, between tradition and innovation, between East and West -- none of these oppositions captures the meat of the debate but each is a facet. Here we hear the last words of the murderer and discover his identity -- and we hear the three master miniaturists composing an elegy for Master Osman's workshop and for the vanishing art of illumination. And there are moments where the narrative perspective shifts slightly and I can hear Pamuk speaking in his own voice about his writing. I feel like I am staring into the abyss. I am very much looking forward to reading the final chapter. Pamuk is a master of tragedy.

posted afternoon of September 16th, 2007: Respond

|  |

Thursday, September 20th, 2007

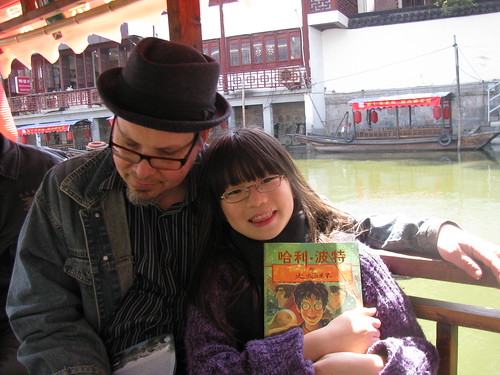

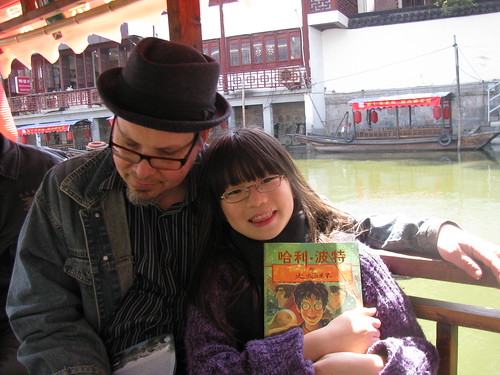

I went over to Montclair Book Center today and picked up a wealth of Pamuk: The White Castle, The New Life, The Black Book, and his new collection of essays, Other Colors. First thing I read was his notes on My Name is Red, written during an airplane flight immediately after he finished checking the final copy. He says he is worried about the outer story of the novel, "that the mystery plot, the detective story, was forced, and that my heart wasn't in it, but it would be too late to make changes." I can totally understand him feeling that way -- it seems to me like it must have been a huge amount of work integrating the two stories and getting the product to flow naturally. He offers his aplogies to "my poor miniaturists" for "the intrusion of a political detective plot that would make my novel easy to read." But he doesn't need to worry about it (well obviously, duh, he won the Nobel Prize...), the outer story not only makes the book easier to read, but adds layers of meaning and beauty to it. I posted at KIDLIT about reading some of these essays to Sylvia.

posted evening of September 20th, 2007: Respond

➳ More posts about The New Life

|  |

Sunday, July 6th, 2008

At the end of the second chapter of Autobiographies of Orhan Pamuk I learn that Other Colors, ostensibly a translation of Pamuk's 1999 collection Öteki Renkler: Seçme Yazılar ve Bir Hikaye, is actually a separate collection, with only about a third of the contents taken from the older book.* All the essays on Turkish literature and politics were omitted from the English version. Replacing them were... assessments of the works of authors he admires -- ranging from Fyodor Dostoyevsky to Salman Rushdie -- ...others are autobiographical or contain thoughtful reflections on his own novels. This is surprising to me. I like the selection in Other Colors; but I'd be very interested to read Pamuk's essays on Turkish literature and politics as well. McGaha quotes a passage from Pamuk's essay (which he had written in 1974, at the outset of his career) on the Turkish author Oğuz Atay: Pamuk argues that critics were bewildered by the novelty of Atay's novels, in which the author's voice and attitude, his peculiar tone of intelligent sarcasm, were more important than plot or character development. What is most distinctive about these novels is their style:When the novelist puts the objects that he saw into words in this or that way, what he is doing is a kind of deception that the ancients called "style," manifesting a kind of stylization. There are deceptions every writer uses, like a painter who portrays objects. This is the only way I can explain Faukner's fragmetation of time, Joyce's objectification of words, Yaşar Kemal's drawing his observations of nature over and over. Talented novelists begin writing their real novels after they discover this cunning. From the moment that we readers catch on to this trick, it means that we understand a little bit of the novelistic technique, what Sartre called "the writer's metaphysics." This passage seems pretty key to an understanding of My Name is Red, and how it fits in with Pamuk's other novels. I'm sorry to see neither of Atay's novels has been translated into English.

* A little thought makes it obvious that many of the essays in Other Colors could not have appeared in the earlier collection, dealing as they do with events occuring in 2005 and later. My grasp of Pamuk's timeline was not as firm when I first looked at this book as it is now. I also went back just now to reread the preface, which makes clear that this is a separate work from the earlier collection. Look at its beautiful final paragraph: I am hardly alone in being a great admirer of the German writer-philosopher Walter Benjamin. But to anger one friend who is too much in awe of him (she's an academic, of course), I sometimes ask, "What is so great about this writer? He managed to finish only a few books, and if he's famous, it's not for the work he finished but the work he never managed to complete." My friend replies that Benjamin's œuvre is, like life itself, boundless and therefore fragmentary, and this was why so many literary critics tried so hard to give the pieces meaning, just as they did with life. And every time I smile and say, "One day I'll write a book that's made only from fragments too." This is that book, set inside a frame to suggest a center that I have tried to hide: I hope that readers will enjoy imagining that center into being.

posted afternoon of July 6th, 2008: Respond

➳ More posts about Other Colors

| More posts about My Name is Red

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |