|

|

Saturday, April 17th, 2010

Last month's issue of Words Without Borders has newly-translated poetry by a Chilean poet and an Argentine: "Tales of Autumn in Gerona" is Erica Mena's translation of Bolaño's "Prosa del otoño en Gerona," excerpted from the forthcoming Tres (which Bolaño considered to be one of his best books); and "Roosters and Bones" is Elizabeth Polli's translation of "Gallos y huesos," by Sergio Chejfec. And, well, lots more too -- Words Without Borders is consistently full of interesting stuff.

posted evening of April 17th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Roberto Bolaño

|  |

|

On re-reading, I find the last third of "Last Evenings on Earth" confusing. It seems like there is supposed to be some confusion, like that's the point of it -- the title suggests (and B seems to be worried) that B and his father die in Acapulco; but I'm pretty sure (though the ending is totally open) that's not what is going to happen, rather it's some element of their relationship that is dying. Bolaño sets this up at the beginning of the final section of the story when he says, There are things you can say and things that can't be said, B thinks, depressed. From this moment on, he knows that he is approaching the disaster. ... And here ends the parenthesis, here end the forty-eight hours of grace, when B and his father have visited the bars of Acapulco, have slept on the beach, worn out, have eaten and even laughed; here begins an icy period, a period seemingly normal but dominated by some frozen gods (gods who otherwise never interfere with the heat which reigns in Acapulco), a few hours which in another time, perhaps when he was a teenager, B would have called boredom, but nowadays he would never use that term; more likely disaster, a peculiar sort of disaster, a disaster which on top of everything else will distance B from his father -- the price they have to pay to live.

-- there's a lot strange about this paragraph -- why is this "the price they have to pay to live"? -- but I'm primarily interested in the notion that B is being further distanced from his father here. The theme of the whole trip seems to have been B distancing himself from his father; at the end they seem if anything a little closer than over the course of the trip. Look at the penultimate paragraph of the story: B thinks of Gui Rosey, who disappeared from the planet without leaving a trace, docile as a lamb while the Nazi's hymns rose up to a blood-red sky, and sees himself as Gui Rosey, a Gui Rosey buried in some vacant lot in Acapulco, disappeared forever, but then he hears his father, who is making some accusation to the ex-clavadista, and he realizes that unlike Gui Rosey, he is not alone. This has the feeling of an important moment for B, the moment where he grows closer to his father (and given the barroom-brawl setting, it must be said there is a lot of potential for this to be corny) -- but the moment has been set up as one of further alienation. So I come away from the story not sure what to make of it -- B's defining characteristic is his passivity, his father's might be his boorishness or it might be his cool-headedness "when it counts." I feel for B and hope he has a better time on his next vacation...

posted evening of April 17th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Putas asesinas

|  |

|

The high frequency in "Last Evenings on Earth" of the word clavadista (diver) makes me think about Bolaño's poem Resurrection: "Poetry slips into the dream/

like a dead diver/

into the eye of God." The word translated as "diver" here is buzo; I wonder what the distinction is. Is clavadista specifically a "cliff diver"? Is buzo a deep-sea diver? The high frequency in "Last Evenings on Earth" of the word clavadista (diver) makes me think about Bolaño's poem Resurrection: "Poetry slips into the dream/

like a dead diver/

into the eye of God." The word translated as "diver" here is buzo; I wonder what the distinction is. Is clavadista specifically a "cliff diver"? Is buzo a deep-sea diver?

Update: Yes, I think (based on Google image results) that it's a distinction between clavadista="an athlete who jumps gracefully into the water" and buzo="an explorer who wears a scuba suit and pokes around underwater" -- the fact that both of these are "diver" in English is coincidental, it's not part of the source material. Actually this makes the imagery in "Resurrection" a lot easier to understand.

posted afternoon of April 17th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Translation

|  |

Friday, April 16th, 2010

In "Last Evenings on Earth," there's some ambiguity about the nature of the book B is reading. It's identified as a book of French Surrealist poetry with pictures and brief bios of the authors; but the long paragraph about Gui Rosey's disappearance reads like a summary of the book, and the book being summarized sounds more like Savage Detectives than like a brief biographical sketch. Perhaps what is being summarized is what's going on in B's imagination as he reads...

posted evening of April 16th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Readings

|  |

Thursday, April 15th, 2010

Werner Herzog's next film will be a documentary about the cave paintings at Chauvet-Pont-D'Arc. The Guardian's Film Blog has more information, plus some videos of him talking about the project. Also check out Roger Ebert's journal (IIUC Ebert is the videographer here), where he writes up a recent screening of Aguirre, the Wrath of God with Herzog and Bahrani, and mentions Plastic Bag. Werner Herzog's next film will be a documentary about the cave paintings at Chauvet-Pont-D'Arc. The Guardian's Film Blog has more information, plus some videos of him talking about the project. Also check out Roger Ebert's journal (IIUC Ebert is the videographer here), where he writes up a recent screening of Aguirre, the Wrath of God with Herzog and Bahrani, and mentions Plastic Bag.

posted afternoon of April 15th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Movies

|  |

Monday, April 12th, 2010

I knew nothing about this book or about this author, until I read Borges' foreword today. Now I want to seek it out and read it... This translation is fairly close to literal, it seems to work pretty well in this case.

From Parmenides of Elea until today, idealism -- the doctrine which affirms that the universe, including time and space and perhaps ourselves, is nothing more than an appearance or a chaos of appearances -- has been professed in diverse forms by many thinkers. Perhaps nobody has educed it with greater clarity than bishop Berkeley; nobody with greater conviction, desperation, and satiric force than the young Scot Thomas Carlyle in his intricate Sartor Resartus (1831). This Latin can be rendered as The Patched Tailor or Mended Tailor; the work is no less singular than its name.

Carlyle invokes the authority of an imaginary professor, Diogenes Teufelsdröckh (Son of God Droppings of the Devil), who publishes in Germany a vast volume dealing with the philosophy of sand*, which is to say appearances. The Sartor Resartus, hardly more than two hundred pages, is a mere commentary and compendium of this gigantic work. Cervantes (whom Carlyle had read in Spanish) had attributed the Quixote to a Moorish author, Cide Hamete Benengeli. This book includes a pathetic biography of Teufelsdröckh, in reality a cryptic, secret autobiography, full of jokes. Nietzsche accused Richter of making Carlyle the worst writer in Britain. The influence of Richter is evident, but he was no more than a dreamer of tranquil dreams, not infrequently tedious, where Carlyle is a dreamer of nightmares. In his history of English literature, Saintsbury holds that the Sartor Resartus is the logical extension of a paradox of Swift's, in the profuse style of Sterne, master of Richter. Carlyle himself mentions the connection to Swift, who wrote in A Tale of a Tub that certain pieces of ermine hide and a wig, placed together in a certain fashion, make up what we call a judge, just as a particular combination of black satin and Cambray is called a bishop. Idealism affirms that the universe is appearance; Carlyle insists that it is a farce. He was an atheist and believed he had disavowed the faith of his parents; as Spencer observed, his conception of the world, of man and of behavior shows that he never ceased to be a rigid Calvinist. His gloomy pessimism, his ethics of iron and fire, are perhaps a Presbyterian heritage; his mastery of the art of the insult, his doctrine that history is a Sacred Scripture which we continually decipher and transcribe and in which we are also written, prefigures -- fairly precisely -- Leon Bloy. He prophecied, in the middle of the Nineteenth Century, that democracy is a chaos at the mercy of the electoral urns, and counseled the conversion of all the bronze statues into bathtubs. I know of no book more ardent, more volcanic, more weary with desolation, than Sartor Resartus.

(The literal translation falls down a bit in the final paragraph, I need to go over that a bit more...)

* (Maybe worth noting in this regard that 30 years later, Borges would title one of his last works of prose The Book of Sand. Or maybe just a coincidence... The first story in The Book of Sand does make a passing reference to Sartor Resartus FWIW.)

posted evening of April 12th, 2010: 3 responses

➳ More posts about Prólogos

|  |

Sunday, April 11th, 2010

Opening up Borges' Prólogos, one of the first things that caught my eye was his foreword to the Spanish edition of Bradbury's Martian Chronicles, first published in 1955. I don't think of Borges as a science-fiction author though some of his stories certainly fit in the genre. Have not read Martian Chronicles since I was 15 or something!-- but I remember reading it a couple of times as a young kid... Perhaps it's worth revisiting.

In the first Century of our era, Lucian composed a True History, which contained among other things, a description of the Selenites, who (according to the truthful historian) spin and card metals and glass, remove and replace their eyeballs, and drink juice of air or fresh-squeezed air; at the beginning of the 16th Century, Ludovico Ariosto imagined a knight discovering on the moon all that had been lost on earth: the tears and sighs of lovers, time wasted in play, unsuccessful projects, unsatisfied longings; in the 17th Century, Kepler published his Somnium Astronomicum, presented as the transcription of a book read in a dream, whose prolix pages reveal the forms and habits of the moon-dwelling serpents -- they shelter themselves from the heat of the day in deep caverns, and emerge at dusk. Between the first and second of these imaginary voyages, one thousand three hundred years elapse; between the second and the third, some hundred -- the first two are, essentially, free, irresponsible invention, while the third seems weighted down by an effort at verisimilitude. The reason is clear: for Lucian and for Ariosto, a journey to the moon is the symbol or archetype of the impossible; for Kepler, it is already a possibility, as it is for us. Wouldn't universal language inventor John Wilkins soon publish his Discovery of a World in the Moone: a discourse tending to prove that 'tis probable there may be another habitable world in that planet, with an appendix entitled, Discourse on the possibility of a voyage? In the Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius, one reads that Arquitas, the Pythagorean, built a wooden dove which could fly through the air; Wilkins predicted that a vehicle of analogous mechanism would carry us one day to the moon. Between the first and second of these imaginary voyages, one thousand three hundred years elapse; between the second and the third, some hundred -- the first two are, essentially, free, irresponsible invention, while the third seems weighted down by an effort at verisimilitude. The reason is clear: for Lucian and for Ariosto, a journey to the moon is the symbol or archetype of the impossible; for Kepler, it is already a possibility, as it is for us. Wouldn't universal language inventor John Wilkins soon publish his Discovery of a World in the Moone: a discourse tending to prove that 'tis probable there may be another habitable world in that planet, with an appendix entitled, Discourse on the possibility of a voyage? In the Attic Nights of Aulus Gellius, one reads that Arquitas, the Pythagorean, built a wooden dove which could fly through the air; Wilkins predicted that a vehicle of analogous mechanism would carry us one day to the moon.In its anticipation of a possible or probable future, the Somnium Astronomicum prefigures (though I would not confuse one for the other) the new narrative genre which the Americans of the north term science-fiction or scientifiction* and of which these Chronicles are an admirable example. They deal with the conquest and colonization of the planet. This arduous enterprise of future men seems meant for epic treatment; Ray Bradbury prefers (without enunciating this choice, perhaps; the secret inspiration of his genius) an elegiac tone. The Martians, who at the opening of the book are horrific, merit pity by the time we reach their extinction. Humanity wins; the author does not rejoice in this victory. He speaks with mourning and disappointment of the future expansion of the human lineage over the red planet -- which his prophecy reveals to us as a vast desert of blue sand, checkered with the ruins of cities and yellow sunsets and ancient ships which sailed over the sand. Other authors choose a date in the future and we do not believe them, for we know we're dealing with a literary convention; Bradbury writes 2004 and we feel the weight of it, the fatigue, the vague, vast accumulation of the past -- the dark backward and abysm of Time of Shakespeare's verse. Already it was heard in the Renaissance, from the mouths of Giordano Bruno and of Bacon, that we are the true ancients, not the men of Genesis or of Homer. What did this man from Illinois do, I'm wondering, as I close the pages of his book, that these episodes of the conquest of another planet fill me with such terror and loneliness? How can these fantasies touch me, and in such a close, intimate manner? All literature (I will dare to venture) is symbolic: there are a few fundamental experiences, and it makes little difference whether an author, in communicating them, chooses the "fantastic" or the "real," chooses Macbeth or Raskolnikov, chooses the invasion of Belgium in 1914 or the invasion of Mars. What is important about the novel, the novelty, of science-fiction? On this book, this apparent phantasmagoria, Bradbury has stamped his long, empty Sundays, his American tedium, his solitude, just as Sinclair Lewis stamped his on Main Street. Perhaps The Third Expedition is the most troubling story in this volume. Its horror (I suspect) is metaphysical; the uncertainty over the identity of Captain John Black's hosts insinuates -- uncomfortably -- that we can know neither who we are nor how God sees us. I would like also to point out the episode entitled The Martian, which contains a pathetic variation on the myth of Proteus. Around 1909 I read, with fascination and fear, in the darkness of an old house which is no longer standing, The First Men in the Moon, by Wells. These Chronicles, though very different in conception and in execution, have given me the opportunity to relive, in the last days of autumn of 1954, those delicious terrors.

* Scientifiction is a monstrous word in which the adjective scientific and the substantive fiction are amalgamated. Jocosely, the Spanish idiom generates analogous formations; Marcelo del Mazo speaks of grÃngaro orchestras (gringos + zÃngaros), and Paul Groussac of the japonecedades which obstruct the museum of the Goncourts.

(I'm noticing as I work my way through this piece, my reluctance to divide a sentence where the original has a single sentence. I'm happy to change punctuation -- it seems to me like Spanish frequently reads better in English with stronger punctuation, semicolon where there is a comma or "and" in the original, dash where there is a semicolon -- but I am averse to putting in extra periods. Similarly -- even moreso -- with paragraph divisions.)

posted afternoon of April 11th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Jorge Luis Borges

|  |

Saturday, April 10th, 2010

While I'm thinking of it, another story I really enjoy from The Black Sheep and other fables:

At first, faith moved mountains only as a last resort, when it was absolutely necessary, and so the landscape remained the same over the millennia.But once faith started propagating itself among people, some found it amusing to think about moving mountains, and soon the mountains did nothing else but change places, each time making it a little more difficult to find one in the same place you had left it last night; obviously this created more problems than it solved. The good people decided then to abandon faith; so nowadays the mountains remain (by and large) in the same spot. When the roadway falls in and drivers die in the collapse, it means someone, far away or quite close by, felt a light glimmer of faith.

posted evening of April 10th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about The Black Sheep and other fables

|  |

|

This is the second story in The black sheep and other fables -- the story of which Isaac Asimov says (and I'm dying to know now whether this book has been published in translation, or if Asimov reads Spanish...)* that after reading it, "you will never be the same again."

In the jungle there once lived a monkey who wanted to write satire.He studied hard, but soon realized that he did not know people well enough to write satire, and he started a program of visiting everyone, going to cocktails and observing, watching for the glint of an eye while his host was distracted, a cup in his hand. As he was most clever and his agile pirhouettes were entertaining for all the other animals, he was received well almost everywhere; and he strove to make it even moreso. There was no-one who did not find his conversation charming; when he arrived he was fêted and jubilated among the monkeys, by the ladies as much as by their husbands, and by the rest of the inhabitants of the jungle too, even by those who were into politics, whether international, domestic or local, he invariably showed himself to be understanding -- and always, to be clear, with the aim of seeing the base components of human nature and of being able to render them in his satires. And so there came a time when among the animals, he was the most advanced student of human nature; nothing got by him. Then one day, he said: I'm going to write against thievery, and he went to see the magpies; and at first he went at it with enthusiasm, enjoying himself and laughing, looking up with pleasure at the trees as he thought about what things happen among the magpies -- but then on second thought, he considered the magpies who were among the animals who had received him so pleasantly -- especially one magpie, and that they would see their portrait in his satire, however gently he wrote it.. and he left off doing it. Then he wanted to write about opportunists, and he cast his eye on the serpent, who by whatever means (auxiliary to his talent for flattery) managed always to conserve, to trade, to increase his posessions... But then some serpents were friends of his, and especially one serpent; they would see the reference. So he left off doing it.

Then he thought of satirizing compulsive work habits, and he turned to the bee, the bee who works dumbly and without knowing why or for whom; but for fear of offending some of his friends of this genus, and especially one of them, he ended up comparing them favorably to the cicada, that egotist who will do nothing more than sing, sing, who thinks himself a poet... and he left off doing it.

Then it occurred to him, he could write against sexual promiscuity, and he directed his satire against the adulterous hens who strut around all day restlessly looking for roosters; but then some of them had received him well, he feared hurting them, and he left off doing it.

In the end he came up with a complete list of human failings and weaknesses, and he could not find a target for his guns -- they were all failings of his friends who had shared their table with him, and of himself. At that moment he renounced his writing of satire, and began to teach mysticism and love, this type of thing; but this made people talk (you know how it is with people), they said he had gone crazy, they no longer received him as gladly or with such pleasure.

* Yep, looks like it was published in English in 1971.

posted evening of April 10th, 2010: Respond

➳ More posts about Augusto Monterroso

|  |

|

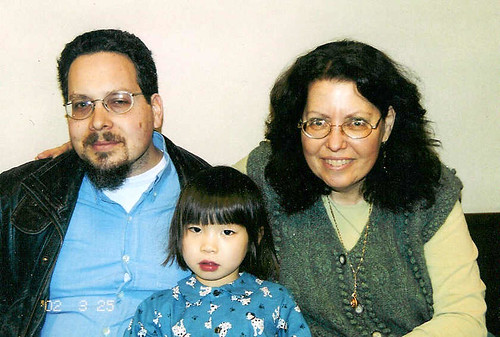

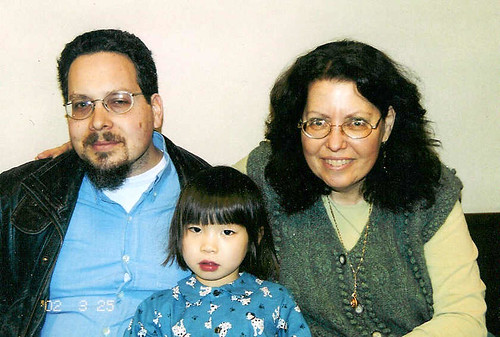

We're back from vacation! Pictures soon. I have a whole lot of new reading material on hand... While we were in Modesto I visited my childhood hangout Yesterday's Books (it seemed so much smaller...) and got a cheap copy of Paradise Lost, which Mark (on Good Friday!) convinced me I ought to read. It certainly is easy to read -- not sure how much I am getting out of it, but it rolls in through my eyes quite easily. In San Francisco we visited Ellen's old friend Maryam, who gave us copies of her new book Returning to Iran -- a look at events there from an expatriate's eye. Reading the first few pieces I am interested and looking forward to the rest.

Also in SF, I visited Libros Latinos on Mission and 17th, and picked up a bunch of books. They are a used book store specializing in Spanish and Portuguese lit with (seemingly) an academic target market. Definitely worth dropping in if you are in the area, a beautiful selection. I got:

- Prólogos con un prólogo de prólogos by Borges -- forewords that he has written for a wide variety of books, published in 1974. Cervantes, Whitman, Swedenborg, MartÃn Fierro, Ray Bradbury(!), his own translation of Kafka...

- MartÃn Fierro -- no idea if I will ever actually get to the point of understanding this, it seemed like a nice book to have on hand while I'm trying to understand Borges.

- Putas asesinos by Bolaño

- The black sheep and other fables by Augusto Monterroso (who will be the first author Bolaño has hipped me to) -- these are pleasant little fables about (mainly) animals. The blurbs on the back, from GarcÃa Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, and Isaac Asimov(!), might be the most compelling pull-quotes I've ever seen.

- I did not buy, because of the price, Borges Laberintos DruÄmelić, which is "The Immortal" and "The Circular Ruins" illustrated with stunning color plates of the paintings of Zdravko DruÄmelić -- if you're looking to buy me a present, look no further.

- The steep markdown which Libros Latinos offers on cash transactions meant I still had enough money in my pocket to stop at Nueva LibrerÃa México down the street and get a copy of Don Quixote.

...Arrived home lugging a big bag of books (Ellen and Sylvia also did some book shopping on the trip), and found on my doorstep a book I had ordered a while back from a used-book seller, Raul Galvez' From the Ashen Land of the Virgin: conversations with Bioy Casares, Borges, Denevi, Etchecopar, Ocampo, Orozco, Sabato. My shelves are full!

posted evening of April 10th, 2010: 2 responses

➳ More posts about Book Shops

| Previous posts

Archives  | |

|

Drop me a line! or, sign my Guestbook.

•

Check out Ellen's writing at Patch.com.

| |